This year’s American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine annual conference was itself an example of technological improvisation, with virtual delegates attending online due to the pandemic. One of the recurring themes of its numerous seminars was the medical necessity for reinvention of traditional rehabilitation models and the involuntary shift of providers towards caretech solutions for reasons of business continuity and infection control.

Case studies

We saw and heard of various caretech projects including:

- Talking therapy for chronic pain by telephone and video. One Washington-based institution reported significantly greater patient adherence to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with comparable working relations to face-to-face sessions and high patient satisfaction.

- An Indiana study into the feasibility of group education via telemedicine for brain injury survivors and care givers, where remote location or lack of transportation was otherwise a barrier to rehabilitation. The feedback showed perceived quality of life improvement, increased self-efficacy, and comparable results to in-person sessions.

- An Atlanta rehabilitation hospital with an online patient therapy management programme, harnessing connected devices for remotely monitoring compliance, such as hand strengthening by wearing a therapy glove and playing Guitar Hero. The behavioural data from usage statistics over time was being analysed to continuously redesign the technology and level of therapist intervention, in order to maximise engagement.

- Remote education and training for families of PDOC patients no longer willing or able to attend clinic, because of shielding their vulnerable relative.

- ‘Precision rehabilitation;’ where data analytics from wearable technology and MHealth (smart-phone and tablet apps) is used to design better targeted therapy.

The general consensus from rehabilitation providers is that telehealth options are being much more widely deployed and that there are significant funding streams available. It would probably have happened absent the pandemic, but not at the pace that we are currently seeing. The main problem with this is that technology solutions are being made available before clinicians are sufficiently trained to use them.

As a consequence, institutions are having to hurriedly develop their own best practice for successful caretech adoption, which includes initiatives such as staff training, internal product expos, user group meetings, and ongoing competency checks.

Outside of clinical practice, there is concern that some consumer-facing caretech innovations lack a sufficient research base, especially the multitude of health apps available for download via the usual online stores.

Claims crossovers

In the UK, Exchange Chambers and brain injury charity Calvert Reconnections published a report in June 2020 following a survey of 161 senior brain injury solicitors. 63% expressed concern about the long-term viability of virtual rehabilitation.

It is clear that necessity really is the mother of invention and that the pandemic has greatly accelerated changes already taking placing within the rehabilitation and management of catastrophic injuries. The current trend is firmly towards therapy delivery in a home rather than inpatient setting where feasible. The jury is still out on many of the pandemic innovations, however there is clear scope for caretech to facilitate the continuity of rehabilitation and care including:

- Remote case management, typically via video call

- Remote housing or wheelchair assessments

- Remote talking therapies or patient education

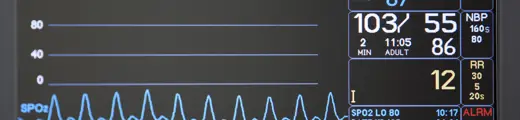

- Physical therapy monitoring via wearable tech

- Home monitoring via smart devices such as webcams and environmental controls

- Personal safeguarding via wearable alarms, fall detectors or GPS trackers.

Compensators should ensure, more than ever before, that providers have sufficient caretech familiarity and knowledge to overcome pandemic obstacles. A flexible and open-minded approach will be required where traditional models may no longer be appropriate, whether temporarily because of infection control measures or permanently because the technological alternative becomes the ‘new normal’.

Healthcare

Healthcare

Life sciences

Life sciences

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

United States

United States