David Froome

Profile

David is a Legal Director in Kennedys’ London office. He commenced his legal career as a clerk with a claimant personal injury firm in 1981. He went on to qualify as a Chartered Legal Executive and then, in 2001, to qualify as a solicitor in England and Wales. David has specialised in clinical negligence cases since 1990.

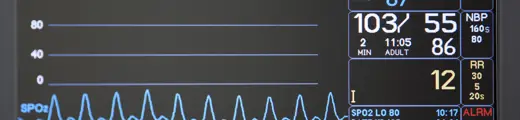

David represents the NHS, medical defence organisations and medical insurers in relation to clinical negligence claims. He specialises in claims concerning cerebral palsy, brain injury and spinal injury cases, but also handles cases encompassing a full range of medical issues. Recent and ongoing cases involve obstetrics, neonatal care, delayed diagnosis of cancer, and surgery. David is experienced at representing NHS trusts, private hospitals and doctors, as well as general practitioners.

Many of the claims involve more than one defendant and David has experience of the tactical issues that commonly arise in such cases. The damages value of many of the claims that David manages are over £10 million. He has a detailed understanding of issues such as multipliers, discount rates, periodical payments and costs.

Qualifications

- Qualified as a Chartered Legal Executive

- Qualified as a Solicitor in England and Wales 2001

David Froome is a senior associate with considerable clinical negligence experience, regularly involved in cases of high value and complexity. Sources say: ‘He has a light touch, a great deal of experience and a great gut feeling for where things are going’

Market recognition

-

Recommended lawyer for 'Clinical negligence: defendant (London)'The Legal 500 UK 2024

-

Recommended lawyer for 'Clinical negligence: defendant (London)'The Legal 500 UK 2023

- Recommended lawyer for 'Clinical negligence: defendant (London)'

The Legal 500 UK 2022 - A Notable Practitioner (Associate to Watch) for ‘Clinical negligence: mainly defendant (UK-wide)’

“David Froome is a senior associate with considerable clinical negligence experience, regularly involved in cases of high value and complexity. Sources say: ‘He has a light touch, a great deal of experience and a great gut feeling for where things are going.’”

Chambers UK 2018

“David Froome frequently represents NHS Trusts in difficult cases including catastrophic injury claims and obstetrics matters. He is singled out by interviewees for his ‘impressive attention to detail’ and for his ‘good mastery for the numbers’ in quantum cases.”

Chambers UK 2016

Awards

Work highlights

- Tomasino v The Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS Trust [2016] – claim brought by mother of identical twins, where both were delivered in good condition, but one died days later from necrotising enterocolitis (NEC). It was alleged there was a failure by the hospital trust to appreciate the deceased was at risk of NEC and it therefore failed to withdraw and wrongly reintroduced enteral feeding. It was claimed that, had the trust adopted a more cautious approach to enteral feeding, the deceased would not have developed NEC and would not have died. The judge found no breach of duty and that NEC was a sporadic and copious disease, which could not have been predicted or reasonably prevented.

- AXX v Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust [2016] – claim was for loss of dependency by the widow and daughter of a young international investment banker, based in London and Russia. He developed acute pancreatitis and was admitted, but a plan for aggressive fluid resuscitation was not instituted and investigations revealed he died due to the hospital trust’s breach of duty. The claim then concerned issues over comparator earners and future career development, but for his early death. This involved experts in employment, forensic accountancy and international tax law. Issues arose over projected earnings, bonuses, investments and the tax regimes over a number of years in the UK, Russia and Italy (where widow and daughter had relocated). Periodical payment order (PPO) was explored, but lump sum settlement was agreed.

- CW v Medway NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust [2017] – high-value case concerning a claimant admitted due to anorexia nervosa exacerbated by recurrent regurgitation and gastritis. The claimant went on to develop spinal tuberculosis (TB) resulting in T4 paraplegia. It was alleged that the claimant would have avoided permanent injury had her TB spinal infection been treated in a timely manner. The case involved expert evidence in disciplines including respiratory medicine, acute medical physician, neurology, neurosurgery and microbiology. The trust served a defence defending the actions of the clinicians and repudiating the claim. Shortly before exchange of witness evidence, the claimant made a ‘drop hands’ offer to discontinue on the basis that all parties bear their own costs. This was rejected and pressed for costs recovery as the claimant was funded by a pre-April 2013 conditional fee agreement. Claimant eventually served a notice of discontinuance and the trust recovered its costs under the terms of the claimant’s after-the-event policy.

- Mansi v King’s College NHS Trust [2011] – case concerned delayed diagnosis of a brain tumour (cavernous sinus meningioma). Issues of medical causation and quantum arose. The case involved expert evidence in disciplines including: neurology, ophthalmology, neuroradiology, oncology, endocrinology, forensic accountancy and care. Settled on advantageous terms (for the defendant) after experts’ meetings when the claimant accepted a Part 36 offer made by the defendant before the experts’ meeting.

- Dwyer v (1) Fong (2) Barking, Havering & Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust (3) Ydrogis Insurance and Reinsurance S.A. [2010] – claimant was an incomplete T6 Frankel C paraplegic following admitted negligent driving of a quad bike while on holiday by the claimant’s partner (D1), and the hospital trust’s (D2) subsequent negligent spinal surgery. Additional holiday insurance had been taken out with D3 to cover quad biking. D1 served a defence alleging D2’s ‘gross negligence’ broke the chain of causation and issued contribution proceedings. Judgment obtained for D2 against D1 on the issue of contribution and striking out D1’s gross negligence defence. D2’s settlement with the claimant included a variable PPO on the basis D2 would be responsible for further damages and/or increased annual payments should the claimant develop “serious symptoms” from a syrinx. D3 paid the maximum under the policy to D2 by way of contribution to the claimant’s damages and paid a contribution to D2’s costs

David.Froome@kennedyslaw.com

David.Froome@kennedyslaw.com

+44 20 7667 9777

+44 20 7667 9777

Download contact card

Download contact card

Healthcare

Healthcare

Public sector

Public sector