Ahead of the general election on Thursday, it is worth taking a step back to review the party manifestos and consider what could be in store for business.

As an initial observation, research indicates that the majority (some 67%) of the British public typically don’t read manifestos or know what they are. However, whilst their publication might not have a serious impact on the outcome of a general election campaign, they are an important turning point for the business community. For the first time, aspirational political parties outline their prospective programmes for government. An analysis of the three main manifestos below shows the varying approaches to the key issues of Brexit, tax, corporate governance and financial and professional services:

Labour

- Renegotiate Brexit deal that includes a customs union within three months in government

- Hold a second referendum on new Brexit deal within six months, with option to Remain.

Liberal Democrats

- Stop Brexit by revoking Article 50 and staying in the EU

- Fight for a second referendum if there is a minority government.

Conservatives

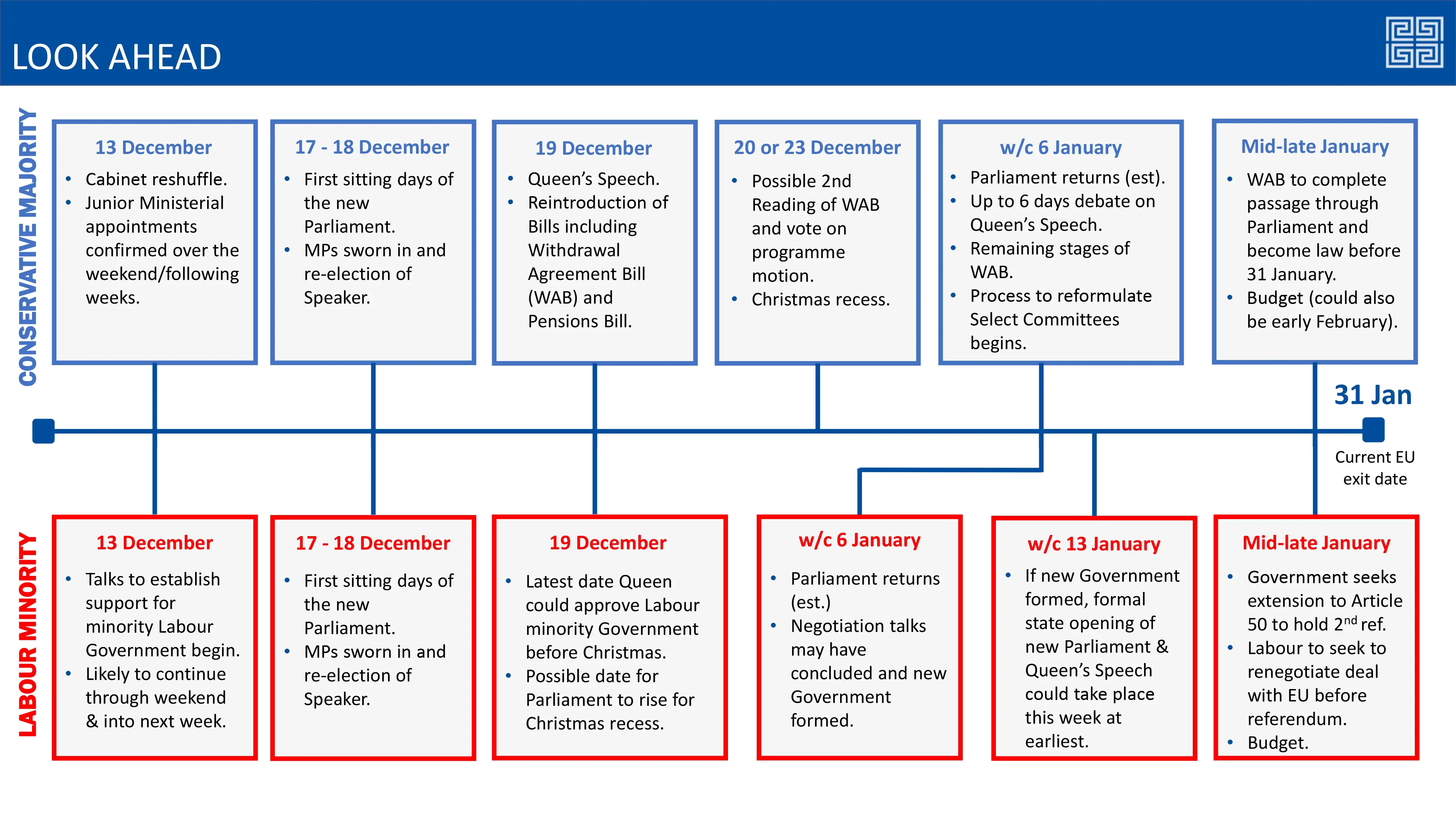

- Table the Withdrawal Agreement Bill in parliament before Christmas, to ensure the UK withdraws from the EU in January 2020

- No extension of the implementation period beyond December 2020.

SNP

- Support a second EU referendum with option to Remain

- Revoke Article 50 if the only alternative is a no-deal Brexit

- Keep Scotland in the Single Market and Customs Union.

Labour

- Increase Corporation Tax to 26% by 2023-24

- Promote fairer international tax rules.

Liberal Democrats

- Increase Corporation Tax to 20%.

Conservatives

- Scrap plans to reduce Corporation Tax by 2% in April 2020.

SNP

- Oppose tax cuts for big business and the wealthiest

- Seek devolution of further tax powers.

Labour

- Put workers on boards and increase board diversity

- Promote employee ownership

- Tackle excessive pay

- Broader ‘public interest test’ to prevent hostile takeovers.

Liberal Democrats

- Give staff in listed companies with 250+ employees a right to request shares

- Put workers on boards in UK-listed companies and all private companies with 250+ employees

- Tackle excessive pay.

Conservatives

- Strengthen the UK’s corporate governance regime

- Reform insolvency rules and the audit regime.

SNP

- Put workers on boards

- Provide statutory basis to enforce climate change-related disclosures in annual reports

- Tackle gender pay gap, including through fines.

Labour

- Overhaul the system of regulation to “ensure that it serves the public interest”

- Introduce a financial transactions tax.

Liberal Democrats

- Legal standards for decarbonisation to encourage green investments

- New powers for regulators to act if banks and other investors not managing climate risks properly.

Conservatives

- Strengthen and reform corporation governance and audit regime

- New powers to Competition and Markets Authority to tackle markets that are failing consumers

- Deregulatory drive in general.

SNP

- Support freeze in further Insurance Premium Tax rises

- Establish an Independent Savings and Pension Commission to ensure policies reflect needs of different regions of the UK.

What would the successful implementation of the ‘winning’ manifesto mean for business?

Conservatives

Responding to the Conservative manifesto, CBI Deputy Director-General Josh Hardie said: “Businesses will be heartened by a pro-enterprise vision” but noted caution around a “needless rush for a bare bones Brexit deal that would slow down our domestic progress for a generation.”

Conspicuous in its absence from the Conservative manifesto were any major commitments that would impact the City. On the campaign trail, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced in a speech to the CBI that a plan to reduce corporation tax by 2% next year would be scrapped. At 19%, the UK’s corporate tax rate is already below the EU average (21.68%) and OECD average (27.63%). It was therefore a decision that was met with little protest in the City, which has not been vocally lobbying on corporation tax given the dominance of Brexit.

In his leadership bid to succeed Theresa May, Boris Johnson sought to promote his pro-business credentials. Often citing his two terms as Mayor of London in which he was a major advocate for financial and professional services, we can expect a majority Conservative government to be seen to act in the interest of business. However, it is expected to focus much more heavily on regulation and legislation that helps small and medium-sized businesses. Whilst maintaining a steady flow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the UK is imperative, the Conservatives will not want to be too friendly to the City or it will play into Labour’s attack lines about wealth and privilege.

Labour

Whereas the Conservative manifesto was seen to be cautious and muted, Labour’s election manifesto is unapologetically radical. Business and economic measures include a vast £400 billion “national transformation fund”, paid for through borrowing, in order to invest in infrastructure and low-carbon technology. Rail, mail, road and broadband would be brought under public ownership with a sale price determined by parliament. Corporation tax cuts made since 2010 would be reversed, whilst high earners in the City would be asked to contribute more heavily in the form of an increase in income tax for those earning more than £80,000.

Tax rises worth more than £80 billion a year by 2023-24 were widely attacked by business groups – CBI Director General Carolyn Fairbairn said “Significant hikes in corporation tax, threats to important investment incentives and windfall taxes on oil and gas will set alarm bells ringing for globally mobile businesses.”

Based on their record in Opposition, there is little to suggest that Labour would lend a friendly ear to business in government, which was largely reflected in their manifesto launch. Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have consistently stated that they will ask big business to “do a bit more” and we can expect the City to be asked to pay a greater share to central government, in an attempt to redistribute wealth and resources around the country.

Liberal Democrats

Before considering Liberal Democrat policies at face value, it is worth considering their likely impact. Since their high point in the polls at 24% on 29 May, the party has been in decline. A reduced share of the vote and a small number of MPs in parliament would limit the ability of the Lib Dems to position themselves as ‘kingmaker’ in the event of a hung parliament.

Addressing professional and financial services, the Liberal Democrats took a bold approach in a similar vein to Labour. Whilst Labour would raise Corporation Tax to 26%, the Lib Dems would increase it to 20%. Further pledges included a crackdown on tax avoidance by multinationals by reforming “place of establishment rules,” and ensuring tax bills are more closely related to the sales companies make in the UK. Those commitments are broadly in line with Labour’s approach, although less radical than a commitment to de-listing companies that fail to tackle the climate crisis from the London Stock Exchange.

In the Cameron-Clegg coalition, it was the Liberal Democrats who ran the Business, Innovation & Skills and Energy & Climate Change departments. Now both moulded into the Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy department, it is feasible that the party could demand a Lib Dem Secretary of State to lead on both business and climate change as their price for propping up a Labour government.

So where are we?

Irrespective of the outcome of the general election, a major trend that we can expect to see develop in 2020 is businesses being asked to do more for their communities and supply chains, whilst better defining their ‘purpose’.

The other aspect to highlight is climate change. Promoting a green economy, including by way of legal standards for decarbonisation, is a policy area that has cross-party support (in one form or other). Given the palpable shift in public concern over the environment, it is of little surprise that governments and political institutions around the world have been prompted to declare climate emergencies.

Overall, therefore, ethical investment and a pivot away from the extractive industries seem inevitable regardless of the political make-up of the next government. With consumer behaviour placing an increasing onus on environmentalism, politics and business will need to mirror their demands to keep pace with a changing society. The pace at which climate change mitigation measures are demanded of big business does of course depend on the outcome of the election, with Labour, for example, pledging more radical and urgent measures than the Conservatives. But whoever occupies 10 Downing Street after the result of 12 December election is announced, business and the City must prepare for another frenzied period of activity – with regard to all policy areas that touch them. From Brexit to specific business policy, there will be no shortage of issues keeping the City on its toes in 2020.

United Kingdom

United Kingdom